This story is an assignment for Motherboard first published in February 2014.

While I say some words about the history of Brazilian funk, Douglas Celestino dos Santos keeps saying, “Yeah, I remember that.”

The producer lives in Cidade Tiradentes, in São Paulo’s far east side. He knows everything that happens in his hood. He was there when MC Dedê blew up on Orkut with 10 different profiles; when the “fluxos,” the funk bloc parties, took over the brick-walled alleys; and more recently, when loló, Brazilian slang for an ether-based aerosol drug, started to take over the minds and lives of Cidade Tiradentes’ youth.

Such was the case with his brother, Mahal Farouq, who died in December 2013 from abusing the drug.

“The doctors said it was cardiac arrest, but they also said it was because of loló. The death certificate listed the cause of death as cardiac arrest,” said Douglas, who’s aware of at least five other similar cases. But whether it’s because they’re underreported or simply unknown, the deaths caused by lança-perfume (another common name for the drug) don’t show up in surveys or studies, and haven’t caught much interest from the authorities. One of the few studies regarding the use of the lança-perfume calls it a silent epidemic.

[aesop_map height=”300″ sticky=”off”]

“You don’t see anyone talking about that, no doctor, no researcher. It’s all left to chance,” said Paulo Malvasi. After getting a PhD in public health, he turned his research to the narcotic dynamics in São Paulo’s suburbs. Between field research and working with social workers, Malvasi has collected a wealth of information on the drug: data on deaths caused by the excessive use of loló, along with stories of how the drug is sold, both at parties and generally shady spots in the city, and stories of the drug’s artisanal or industrial manufacturing processes.

In São Paulo’s central district, the drug has quite a young audience. “The lança has an appeal to the younger kids, from 13 to 15 years old, due to its rapid high, the laughter it causes,” Malvasi said.

“Loló is killing more than the bad guys’ guns or the cops”

Just by going to the parties you can see that’s the real deal. “Whenever I go to a baile funk [parties featuring funk carioca, a Brazilian offshoot of Miami bass] I see lot of kids, and I do mean kids, using it. Wherever you look, there’s someone with a spray can. Wherever you look there’s someone with a bottle of it,” Douglas told me. “There are a lot of essences, so it all depends on the customer’s choice: Strawberry, vanilla, grape, just about everything. There’s no restriction whatsoever.”

Sold in little bottles identical to perfume samples, loló’s price range varies less than its flavors: somewhere between 5 and 10 Brazilian reais (roughly two to five American dollars). “People chip in, and with one buck from each one you get a bottle,” he said.

In case there was a manual on how to use the drug, it’d say shake before using. Shaking cans or bottles, kids can stay up a whole night inhaling ether vapors. It is no accident that some of the reports talk about deaths occurring early in the morning.

“They say ‘he’s dead ‘cause he spent a night out doing loló,’” said Malvasi. The drug kicks so hard that some people pass out a little while after or just fall to the ground. “If you hit your head when falling, it’s almost fatal. The doctors say that because that stuff goes straight into your brain,” said Douglas. He’s right.

“These inhalants pass through the brain mass and cause minor hallucinations and alter the perception for a few minutes, seconds even,” explained Frederico Garcia, a psychiatrist and coordinator for the Drug Reference Center of the Minas Gerais Federal University (UFMG). He’s also a member of the Brazilian Psychiatry Association (ABP), an organization that compiled several studies on inhaled drugs in 2012. The work attested that boys and girls first try loló between 14 and 15 years of age—an average that can go down when kids find themselves in vulnerable situations.

“It’s extremely dangerous to the teenage brain because the brain is building itself slowly. The teenage brain is more tolerant to psychoactive substances such as drugs and may become more impulsive, less tolerant to frustrations”, explained Garcia.

Even though the consequences are near certain, he does not believe that loló consumption by itself causes death, except in cases where there are allergic reactions. “At these parties, the teens end up drinking a lot, not hydrating themselves enough, consuming other drugs and altering their hepatic metabolism,” Garcia said. “Then it gets risky, but it is not just one drug that leads to death.”

[aesop_chapter title=”CHECK OUT THE LANÇA!” bgtype=”img” full=”on” img=”https://maiafelipe.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/LANCA.jpg”]

A specialist told me that in the state of Minas Gerais there are people who use these inhalants to “hear the bells,” which is an allusion to the humming sound one hears right after inhaling. In São Paulo, they call it the tuim. In Pernambuco, loló got nicknamed sucesso (success). All it takes is a little spin around Recife or Olinda during Carnival to smell the lança. I lost count of how many kids I’ve seen selling the stuff like water in the desert on the cramped and crowded streets of Carnival festivities. The price doesn’t vary that much compared to São Paulo, but the recipe does. No one knows quite for sure what loló is.

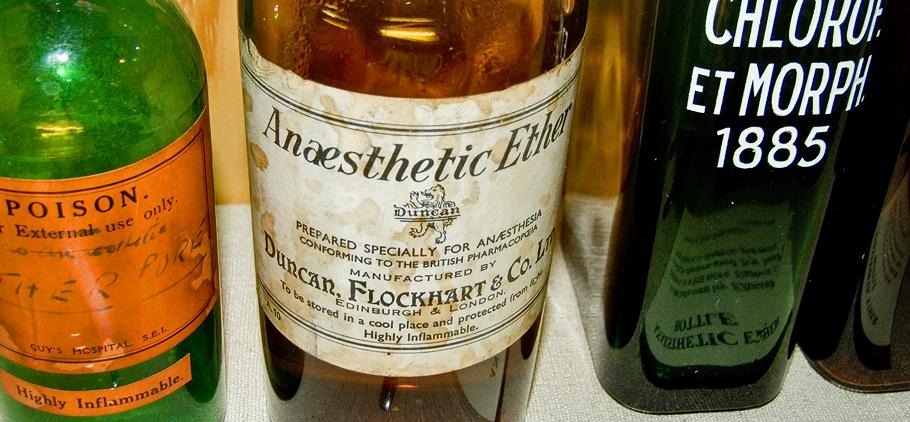

“The composition of these drugs varies a lot. It’s generally a mixture of alcohol, ether and chloroform in different portions,” explained Garcia, certain that the lança-perfume used nowadays is way more powerful that what the people on the good ol’ Carnival balls used back in the day.

We reached out for the São Paulo State Department for the Prevention and Repression of Narcotraffic (DENARC) to try to get a better grasp of what the lança is made of, but the response was fairly limited. “The lança-perfume is a drug manufactured with chemical solvents based on ethyl chloride,” DENARC told Motherboard Brazil.

The organization gave further details, however, regarding the operations conducted to control the drug. According to DENARC, 31 opiate seizures were made in São Paulo in 2014, an increase of 100 percent compared to the previous year. There were just 13 arrests that mentioned the term loló, but there was a 200 percent increase in the number of ops carried out. The official note also states that 1,114 bottles of the substance were apprehended, and points out the fact that there will be a larger focus on the drug this year—especially during February, when Carnival happens.

In the meantime, it’s clear that some of the manfucturing of this inhale-only version of Breaking Bad is controlled by Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC), one of Brazil’s largest crime organizations. During his research, Malvasi even got to see lança-perfume being sold next to marijuana, cocaine and crack at some dealers’ corners. He the drug is a well-oiled cog on this rather productive crime machine.

“A substance that has a repetitive use, which is cheap to produce, which does not depend upon criminal structures for international transportation, ultimately, all these factors combine to increase the profit and minimize the risk for the organizations,” he told me.

According to Malvasi, there are independent manufacturers running makeshift operations or small plants to produce lança-perfume. The documentarian Renato Barreiros confirmed that finding.

“In each and every hood there’s someone who makes it. And there’s the great danger,” he said. “There’s no formula, some dude sniffs it and dies. And since it all has some kind of essence or flavoring, you just can’t smell the solvent.”

Barreiros documented the Brazilian funk scene in São Paulo in the films Funk Ostentação – O Filme and NoFluxo. “Lança means for funk the same that ecstasy meant to the rave scene, but just like in the raves, it doesn’t mean that everyone is high on it,” he said.

One character that pops up and also participates in the soundtrack of both documentaries is MC Bin Laden. The funkeiro has at least three tracks with “lança” mentioned in the title and it’s impossible to keep count of how many times the drug is cited in his lyrics with a poetical flair regarding flavors, metaphors, and synonyms.

When we chatted, Bin Laden told me he didn’t use lança-perfume. “I just make music hitching on other people’s highs,” he said. And it was in that high that Bin Laden rose to fame, becoming one of the biggest in São Paulo’s new funk scene, along guys like MC Brinquedo and MC Pedrinho.

Even the Passinho do Romano (Roman Step), a dance that’s not quite at Harlem Shake levels of virality yet, seems to originate from the lança-perfume high.

“Vai descendo até o chão/Deixa os braços a desgovernar” (Get down to the floor / Let your arms go loose), sings MC Crash in “Sarrada no Ar.”

“The music sings about what’s happening. Lança was here before. MC Bin Laden said that his verse for ‘Lança de Maracujá’ came from a guy selling this stuff at a party,” said Barreiros.

Loló may be the current frenzy in São Paulo, but it isn’t exclusive to any particular venue. Used in balls since the beginnings of 20th century, lança-perfume was banned during the Jânio Quadros government with claims that the substance, described as ethyl chloride, was hazardous to health. Since then the drug traveled all over Brazil on the backs of college parties, or sniffed with the aid of handkerchiefs on micaretas (off season Carnival-like parties), and not letting go of the feast of the flesh, it came to São Paulo’s funk scene.

In these almost a hundred years of use, the medical community still has trouble dealing with the abuse of inhalants. “The emergency units are always prepared for this kind of thing, but there isn’t the reflex to think of said situation is happening because of drugs,” said Garcia.

For Paulo Malvasi, the public opinion overestimates the use of marijuana, crack and cocaine, whose descriptions of excessive use are less frequent, in favor of a deceptive lightness associated with inhalants. “Something as destructive and violent as the lança-perfume becomes natural,” Malvasi said.

Douglas Celestino dos Santos agrees. “My brother started smoking weed when he was 16, 17. The stronger drug, lança-perfume, came when he was 18. He complained about chest pains, and he couldn’t break. For some, lança is innofensive, weak, but it just as deadly as any other drug.”

Nowadays, a picture of Mahal Farouq, Douglas’ brother, illustrates Fluxo’s page. Created right after the young man’s death, the group tries, amidst the irony of its own name, to educate the youth of Cidade Tiradentes about the fatal blow that a whiff of loló can be.