This is a story assignment for The Guardian. It was first published in October 2021.

Jonathan Ferr thinks back to his youth. “Jazz was giving me freedom, while rap was showing me my place as a Black man in a racist society,” remembers the pianist, part of Brazil’s vibrant contemporary jazz scene. “Those were two Black musics that have brought me power to be myself.”

Like their US forebears, who used jazz to advocate for – and simply experience – freedom in their racist country, Black Brazilian jazz artists such as Ferr are using music to stake a claim for their heritage in a culture that often sidelines it. Despite Brazil’s contributions to jazz – from bossa nova standards to fusion avant-gardists – its Black artists have struggled to succeed (particularly when playing bluntly Afrocentric themes) and many of the most successful proponents have been white or light-skinned. Black talents dismissed by their own country include Dom Salvador, Tania Maria and Johnny Alf. Maria and Salvador left Brazil to make a living as musicians in the US and Europe, while Alf, a bossa nova pioneer, had to sell his belongings to afford treatment for a cancer that eventually killed him. “Brazilian music is Black music,” says jazz pianist Amaro Freitas. “And what happened to these artists was racism.”

Despite this, it is proudly Black musicians who are now setting the tone for their country’s jazz, including Freitas, whose latest album Sankofa (praised by Jazzwise magazine as “magnificent”) features striding piano lines shifting in odd tempos, and mixes melody with traditional Brazilian rhythm in a show of striking technique. “We usually think of the piano as an instrument with 88 keys, but if you think of it as a drum set, there are millions of possibilities,” he says.

Born in Recife, a coastal city in Brazil’s north-east, he joined a small local evangelical church as a drummer aged 11; his father got him to settle down with the keys. The music he played there had a “Christian, European influence, but this church was located in an underprivileged neighbourhood, so there was Brazilian music like forró, brega and funk that influenced me as well.”

He was forced to quit his music school – his family couldn’t afford the monthly £5 fee – but years’ of gigs and music production studies made him hungry to bring Brazilian music into his jazz. In Afrocatu, from the album Rasif, Freitas blends the polyrhythms of folkloric maracatu music with Ornette Coleman-style improv. He argues that “in Brazilian instrumental music we look up to the virtuoso, but this often lacks the aesthetics, the history” of his country’s diverse culture.

This amalgam of sacred practices rooted in Africa and Europe, urban Black culture and traditional Brazilian music, is also a feature of Jonathan Ferr’s work. Sino da Igrejinha, the opening track of his latest album, Cura, is a ponto – a ritualistic chant accompanied by heavy percussion, commonly attributed to Afro-Brazilian religions candomblé and umbanda. The song’s fast-paced descending melody also echoes Asa Branca, a staple in Brazil’s national songbook.

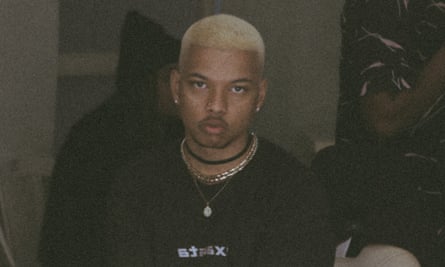

Growing up in Madureira, which he describes as “a place known for strong Black culture”, Ferr had to share his first keyboard – “a cheap toy that my father bought for us” – with his four siblings. Years later, while studying with a scholarship in one of Rio’s conservatories, he started going to his first jazz concerts in the bourgeois clubs of the city’s south side, having to leave before the closing act to catch the last bus. “I was quite often the only Black person attending these performances, and I kept asking myself why that music was only played there and not in Madureira,” he says.

So as well as playing the Blue Note club in Rio and his city’s iteration of the Montreux jazz festival, he staged a concert in his own neighbourhood in 2017, with tickets priced at one Brazilian real (less than 20 pence). “It was crowded!” he says. “People don’t listen to jazz because they don’t have access to it – that has left a mark on me.”

Today, Ferr advocates for a democratic jazz music in Brazil. “But I don’t want to push it down, like many people do when they say they want to bring art to the favelas: I want to do it horizontally.” His 2018 single, Luv is the Way, demonstrates that openness as Ferr’s piano swings from sweet melodies to electrified funk riffs, and like his 2021 album Cura, the track is heavily influenced by Afrofuturism, the art mode that envisions utopian sci-fi futures for Black people. “I’ve been seeking out, in this aesthetic, the idea of bringing Black people to the forefront of their stories,” he says.

Embracing Afrofuturism, and reaching out to pop music festivals and underground clubs, the duo Yoùn and the producer Carlos do Complexo also rely on the jazz idiom in their music-making.

Yoùn, 20-somethings Allison Jazz and Gian Pedro, released the album BXD in Jazz in January. The three-letter abbreviation in the title stands for Baixada, a region located in the outskirts of Rio. Jazz says he came to appreciate how the genre of his name was intertwined with other Black music, “with North American gospel music, with the blues”, and that “once we realised that all of that belonged to us, we started to get our hands on it”. Pedro describes jazz as “a game we both play together”. In tracks such as Inebrio, the duo explore breakbeat patterns and Brazilian percussion sets with soulful R&B harmonies.

A beatmaker, producer and DJ, Carlos do Complexo befriended the duo thanks to their musical like-mindedness. “The kind of music we listen to, in our neighbourhood, is not that usual. People say it’s music for ‘nuts,’” says Carlos. In November 2020, he released his own take on that weird hybrid sound with Shani, an album that encompasses centuries-old Egyptian theology and stories of aliens. “All this jazz music we’ve been absorbing will be reshaped [into] something much more connected to the idea of jazz instead of the genre per se,” Carlos argues, adding that electronic music is still a more accessible road to this music. “It’s way cheaper to become a beatmaker than buying a traditional instrument in Brazil, but I think bringing together these worlds with the jazz idea will give birth to great stuff.”

Ferr, who will perform to thousands at the Rock in Rio festival in 2022, is similarly optimistic after the years of racial inequality and struggle. “When I get on a stage I speak for myself, but also speak for Madureira, for pianists that couldn’t reach that spot, for generations that didn’t have a Black reference like me. We’ve lost too many Brazilian musicians already. The narrative now is as follows: I’m Black, I’m Brazilian, and I will stay in my country telling everyone that making this music is possible.”